CHAPTER 6

RECOMMENDATIONS

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. US Public Law 88-577 (1964 Wilderness Act)

Ithink the largest single need in American forest biology is the study of man's relation to forest land. Our foresters need to understand much more than most of them do about purely human motives and aspirations with respect to the land. They ought to become genuinely knowledgeable and respectful of people's economic, social, and aesthetic institutions. Hugh Raup (Stout 1981)

The following recommendations are based on the findings of this research and my own ideas and interests. They are divided into two sections: recommendations for further scientific research, as suggested by the hypothesis in Chapter 1, the method of multiple hypotheses, as defined in Chapter 2, and the conclusions in Chapter 5; and recommendations for the practical application of methods and findings described in chapters 2, 3, and 4. The intended audience for the first section is agency scientists, university researchers, students, teachers, and interested individuals; for the second section, the intended audience is regional landowners, resource managers, and policymakers.

The research in this thesis was performed in accordance with the "method of multiple working hypotheses" first described by Chamberlin in 1890 (Chamberlin 1965): "the effort is to bring up into view every rational explanation of new phenomena, and to develop every tangible hypothesis respecting their cause and history". Two key features of this methodology are that research questions are answered based on the "weight of evidence", and research findings include the formal identification of additional "tangible" questions as they present themselves. The following recommendations were developed by this process and it seems used in pursuit of most scientific questions based on natural history and/or people.

1) Carrying capacity and precontact human populations

Good population figures for precontact Oregon Coast Range people do not exist. Good information has been developed for early historical time, particularly by Boyd (1990; 1999a), and reasonable estimates have been developed for late precontact time that is based on this evidence (Boyd 1999a; Denevan 1992), but nothing in these estimates addresses the great amount of surplus food resources or the millions of acres of "suitable habitat" that was available to people, yet apparently went unused, in precontact times. Were pre-1492 human populations in the Pacific Northwest much larger than previously thought?

This research has shown that a tremendous amount of seacoast, riverine, and inland plants and animals were readily available as food to people in this region. The habitats that these plants and animals lived in are some of the most productive in the world. One researcher demonstrated that a single food plant, wapato, grown in a single area, Sauvies Island, during historical time was sufficiently productive to support a population of more than 15,000 people a year. And that would exclude the need for those people to fish for salmon, sturgeon, smelt, or eels, hunt seals, elk, deer, birds, or rabbits, to gather acorns or filberts, dig camas, pick berries, gather seed, or trade for a wide variety of other foods obtained along the ocean or further inland.

Even the most generous estimates of precontact Coast Range populations do not account for the establishment and maintenance of hundreds of thousands of contiguous acres of oak savannah, tens of thousands of acres of roots, bulbs, berries, seeds, fruits, and greens systematically arranged throughout all of the river drainages, or the elaborate network of international foot trails and canoe routes that allowed people in large numbers to move quickly and efficiently from place to place, whenever need or desire might dictate.

I think it is possible that a significantly higher number of people than previously estimated may have resided in Oregon Coast Range communities in 1491 and/or before. If so, I think a significant majority of these people may have died from disease or other causes sometime before 1600 or 1650, as partly evidenced by the establishment of large regional tracts of conifer forestland during that time.

If large numbers of people did live here, and if those people managed a much larger area of the landscape than previously thought, then the "16th Century" hypothesis discussed in the summary of Chapter 4 may be tangible. If so, this information should be of particular value to landowners and resource managers concerned with ESA wildlife regulations and/or old-growth habitat management issues. The value such information to managers of precontact artifacts and cultural resources is obvious.

2) Indian burning practices and wildlife habitat

Chapter 3 provided useful maps of precontact vegetation patterns that existed throughout the Coast Range in early historical time. These patterns were established and maintained through thousands of years of Indian burning practices. Areas of regular burning were high in protein and fiber production, in the forms of flowers, seeds, fruits, nuts, greens, roots, and bulbs, and offered a wide range of habit types connected by well-established land trails and water routes. Wild animals flourished in these environments, both in variety and numbers, as evidenced by both archaeological and historical records.

Native wildlife either benefited or adapted to patterns of burning and tillage over time. People shared with wildlife the fruits of this form of land management, to varying degree. Could current valued wildlife populations, including game animals, songbirds, butterflies, and "Threatened and Endangered" (T&E) species, benefit by reintroduction of precontact habitat patterns? Current assumptions regarding precontact vegetation patterns guide much of the coastal land management strategies for spotted owls, marbled murrelets, and coho salmon. If these assumptions are accurate and/or can be refined, then targeted native wildlife species could benefit from this line of research.

3) Fire history research and forest management decisions

This research identified a number of threatened and/or obscure sources of information, including fading memories, 90-year old hand-colored timber cruise maps, collections of 60 to 120 year-old photographs, agency reports, etc. Much of this information has value to resource managers today, particularly with recent considerations of past "reference" conditions, old-growth trees, and native wildlife.

Where can this information be found? Is it worth safekeeping, duplicating, and or/wider distribution? If so, how should it be cited? How can someone else locate this information next time it is needed?

Forest management decisions are often said to be made on "the best information available". Decisions vary significantly between land ownerships and regulatory constraints. Private timberland management decisions are made with different amounts and types of information than Forest Service management decisions; which can vary significantly depending on whether the decision is being made for an AMA (Adaptive Management Area) or a designated Wilderness.

Fire history research is of interest to all forest resource managers because wildfire crosses boundaries of landownership and regulatory control with absolute indifference. Decision-making during times of wildfire management, salvage logging operations, prescribed burning, or other fire-related activity tend to affect all immediate landowners at some level, no matter whose land houses the event or activity. Decisions are usually made with entirely different objectives based on entirely different sets of knowledge and information. Yet the outcomes, both good and bad, are often shared by all. If most pertinent information was made available to all resource managers in a manner that was efficient and allowed for improveed communications among affected parties, better and cheaper decisions could probably be made much faster and easier than processes in place today.

This recommendation focuses on the themes of information location, evaluation, duplication, storage, and retrieval, with a focus on the fire history of the Oregon Coast Range. The questions that need to be asked are the same as in paragraph two, above. I've outlined some of the key considerations in the next few paragraphs, below:

Oral histories. The memories and knowledge of key individuals represent our most threatened and endangered information. It has been 52 years since the last catastrophic fire in the Oregon Coast Range and almost 65 years since foresters and ranchers quit "fern-burning." However, grass seed farmers began burning fields regularly in 1948, and foresters began broadcast burning tree planting sites shortly thereafter. There is a body of knowledge in those enterprises that is being lost. Agency personnel and local residents with knowledge of Coast Range fire history should be contacted, interviewed, recorded, and transcribed ASAP before more of them die, become disabled, or move away. These people are also a primary source of historical records and photos, and the best remaining interpreters of many existing documents.

Maps, photos, and texts. One-of-a-kind colored maps, photos, old reports and other documents need to be identified and safely stored until they can be scanned. Digitized information should be made available to the general public as it is brought into existence, unless determined sensitive and constrained for some reason by the Freedom of Information Act.

Database index. All materials should be inventoried and listed on a computerized database. The proposed "5 Rivers Forest History" model (Bormann et al 2003) database would be a good proposal to develop before more data is entered. Existing databases used by the Siuslaw NF, PNW Research Station, OSU Research Forests, Benton County Historical Museum, USDI BLM, the surveyors of Benton, Lane, and Lincoln counties, and the OSU Oregon Natural Heritage Program are all similar in structure and could be modified easily at this time to develop a common dataset of historical maps, photos, reports, survey notes, contact individuals, etc. A user-friendly database with search and display capabilities, such as the Oregon Websites and Watersheds Project, Inc. (http://www.ORWW.org/OR_LYNX/)l, would make a good common product for these agencies to develop for internal and public access via the Internet.

Stored files. Other useful files regarding reforestation, road building, prescribed fire, wildfire, logging, etc., records are in storage at the USDA Waldport Ranger Station office, the Benton County courthouse, the Oregon State Forester's office, and other locations. They should be systematically inventoried, evaluated, and considered for use as time and resources allow. In the interim, they should be protected against fire, water, shredding, and misplacing.

I performed earlier research that demonstrated a strong correlation between Bretz flood events from 12,800 to 15,000 years ago, to subsequent patterns of human use and development (Zybach 1999: 12-13, 77). This research was limited to a 15,000 acre sub-basin of the Luckiamute River drainage (Soap Creek Valley: see Map 2.01), but showed a pattern that was generally accurate for much of the Willamette Valley floodplain. It also disclosed a 400-foot elevation "shelf" that existed in the study area at a slightly higher elevation than the floodplain and could be found along most neighboring hills and valleys, including those of the adjacent Marys River basin (ibid.: 13). This shelf also showed strong evidence of precontact and early historical use, as indicated by the numbers and locations of artifacts from those times.

Research performed for this thesis in Alsea Valley (Zybach 2002: see Map 2.01), also showed a 400-foot well-used "shelf". Allen (ca. 1989: personal communication) speculated that perhaps the Bretz floods were so deep, they spilled out over the Yamhill-Salmon River divide and partly entered the ocean by that route, rather than by way of the Columbia River. Recent conversations with Swanson (2003: personal communication) seem to discount the likelihood that the Bretz floods entered the Pacific with such force that a "backwater" effect could have inundated local rivers (including the Alsea) and affected topgraphy in that manner. Perhaps the well-traveled "shelf" is not common throughout the Coast Range and its existence in three nearby drainages a coincidence; or perhaps it is common through the region, but has a different source of formation than the Bretz floods. In either instance, the apparent relationship between this geological formation and local human use is interesting.

Of similar interest is the existence of areas of soil in Lincoln County in which conifer trees seem to grow much slower than in other areas (Bormann 2003: personal communication). Many previous assumptions (including my own) were that trees grew relatively fast throughout the Coast Range, with most differences within species related to distance from the ocean, elevation, and rainfall. This possibility could bring past methods of assuming relative tree ages or past fire boundaries based on tree diameters and height, into question.

B. Reintroduction of Indian-type Burning Practices

Indian-type burning practices are daily and seasonal, and involve thousands of acres of land a year. Boundaries and travel routes are established geologically, with river mainstems, shorelines, and ridgelines guiding most human traffic away from home or camp. In addition, a key characteristic of Indian-burning patterns is the absence of straight lines. Any recommendation made to reintroduce Indian-burning practices, therefore, must consider the great amount of land needed to reintroduce such practices on a landscape-scale, and must also consider the least amounts of land needed to reintroduce such practices for aesthetic or cultural purposes.

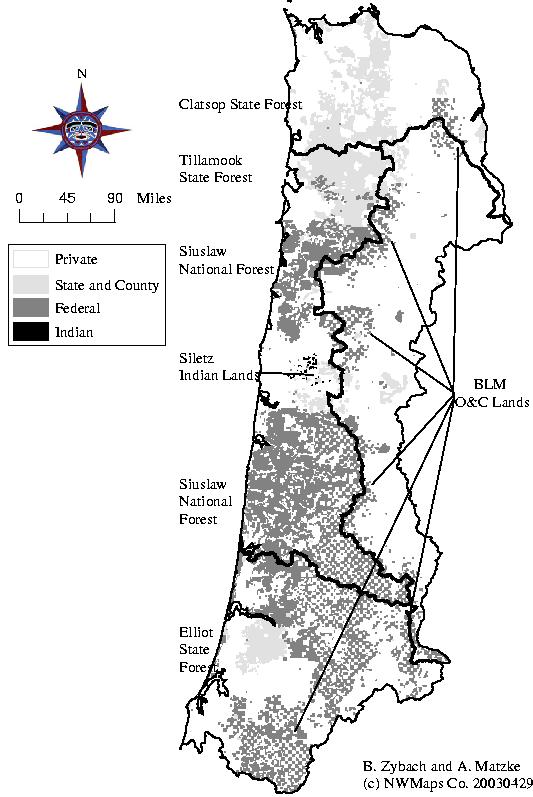

Map 6.01 identifies Oregon Coast Range landowners likely to be most capable of, or most interested in reintroducing Indian-type burning. Large Coast Range landowners include the US Forest Service, USDI BLM, and the Oregon Department of Forestry. As an agency, the US Fish and Wildlife Service has control over many other federal lands, depending on the status of Threatened and Endangered species in an area. Other large landowners include private timberland owners in forested areas of the Range, and grass seed growers in the eastern grasslands. Both types of landowners are familiar with seasonal broadcast burning methods. Siletz, Coquille, Kalapuyan, and Grand Ronde tribes should have a cultural interest in reintroducing past land management activities and producing certain foods, medecines, and basketry materials.

Map 6.01 Land ownership patterns of the Oregon Coast Range, 2003.