CHAPTER

1.

INTRODUCTION: HYPOTHESIS

AND SETTING

It

would be difficult to find a reason why the Indians should

care one way or another if the forest burned. It is quite something else again to contend

that the Indians used fire systematically to "improve" the

forest . . . yet this

fantastic idea has been and still is put forth time and again.

When the forest burned, fires were often

of high intensity and uncontrollable. The tribes of coastal

Oregon were the victims of some of these fires, having been driven

to the waters

of the Pacific Ocean to survive.

James Agee 1993:

56

Between 1840 and 1850 an abrupt transformation

took place in western Oregon that resulted in permanent and large-scale

changes to the region's forest and grassland environments. During

that decade dozens of local American Indian nations and tribes were

all but replaced by a comparatively homogenous population of European

American

immigrants. Many wildlife species were subsequently decimated

and extirpated in favor of domesticated plants and animals: California

condors,

grizzly bears, wolves, and whitetail deer gave way to chickens, cattle

and swine; fields of camas and tarweed were transformed to corn, potatoes

and

wheat. Even

fire was affected. Expansive grasslands that were annually fired

to produce and harvest food crops were plowed and grazed instead. Interior

forestland trails, prairies, meadows, brakes, and berry patches--created

and maintained by fire--were abandoned and began converting to trees. Near

the end of the decade, probably in 1849 or 1850, the first of a century-long

series of catastrophic forest fires took place in the region. These

wildfires were so large and notable they became known as the "Great

Fires" and

acquired individual names: the Yaquina, the Coos, the Nestucca, the Tillamook.

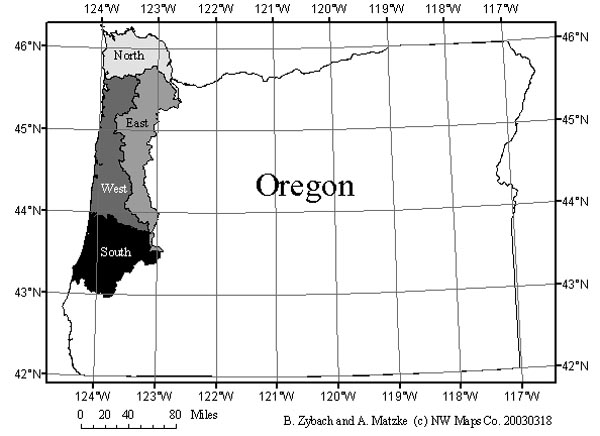

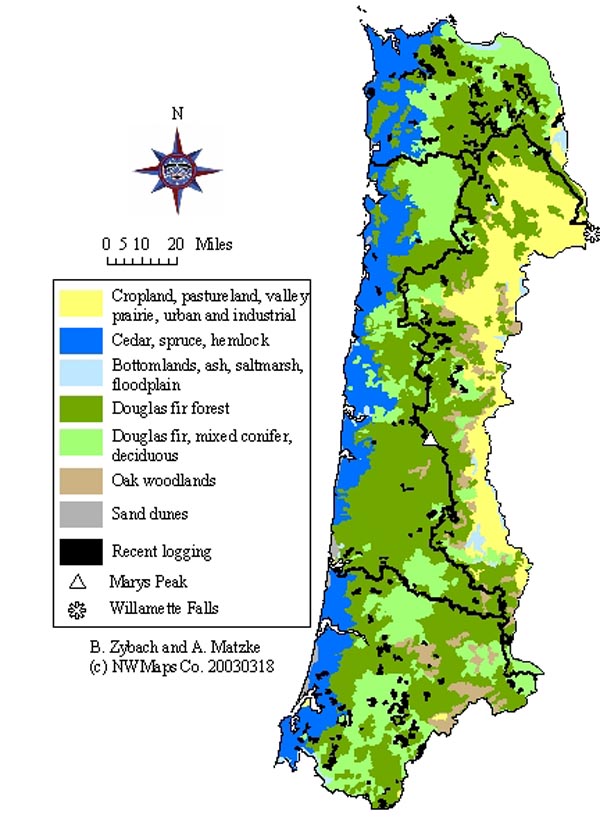

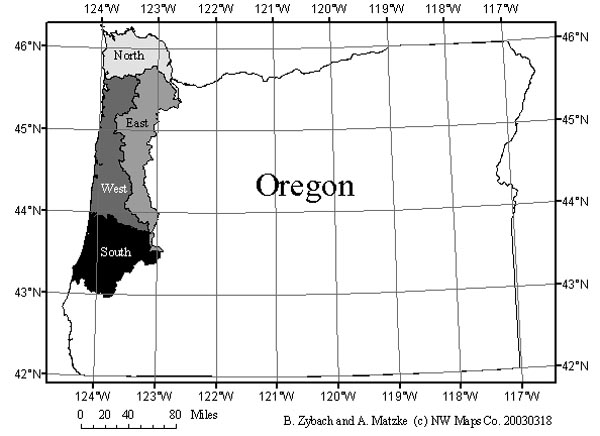

This thesis examines the change in vegetation

patterns of the Coast Range of western Oregon (see

Map 1.01)

from late pre-European contact ("precontact") time: beginning in the

late 15th century, in 1491 (before European diseases were introduced

into North America); through early historical time, until 1951 (the

year of the last significant Tillamook

fire). It

is the first study to place the region's precontact cultural landscape

patterns in context to the fuel histories and boundaries of subsequent

forest wildfires.

A certain amount of history has been written

and documented about the Oregon Coast Range ("Coast Range" or "the

Range") forest fires of ca. 1849 to 1951 (e.g., Gannett 1902;

Morris 1934b; Pyne 1982), but--with the notable exception

of the Willamette

Valley and the eastern slope of the Range--very little has been written

about pre-European contact ("precontact") Indian burning

practices in the area. Eyewitness

accounts of David Douglas from 1825 to 1827 (Douglas 1905; 1906), John

Work from 1832 to 1834 (e.g., Elliot 1925),

by members of the 1841 Wilkes Expedition (Wilkes 1845), and others,

have described the times,

locations

and results

of Indian burning practices along the eastern slope and floodplains

of the Coast Range. Early

paintings (e.g., Warre 1845; Kane 1847) and land surveys (e.g., Preston

1851; Hathorn 1855) added detail to the written descriptions of the

original journalists. Drawing

from these resources, subsequent writers and geographers

(e.g., Morris 1934; Johannessen et al. 1971; Thilenius 1972), have

been able to construct reasonably accurate maps and accounts of

the burning

practices and results of Kalapuyans who occupied the territory (e.g.,

Mackey 1974; Gilsen XX, Boyd

1986). By comparison, very little has been documented

regarding the burning practices of late prehistoric and early historical

people

living

in the northern, western, and southern parts of the region (see

Map 1.01).

Map 1.01 Location

of the Oregon Coast Range study area.

LaLande and Pullen (1999: 267) term Indian

fires in the southern Coast Range "limited and localized" in the "mid-elevation,

mixed conifer forest stands" which characterize the "vast" majority

of the area. Whitlock and Knox (2002: 224) go even further, claiming

the presence

of early historical prairies, savannah, and oak woodlands in the Coast

Range were a direct result of prehistoric climate change and lightning-caused

fires ("which were probably more abundant . . . in the early Holocene":

p.206), and had relatively little or nothing to do with human burning

practices. Through

the use of maps, tables, eyewitness accounts, drawings, and photographs,

this thesis documents the use of fire by American Indian people living

in the Oregon Coast Range at the time of contact with white Europeans

and Americans in the late 1700s. The same methods are used to

describe the subsequent Great Fire events of 1849-1951 and the roles

Indian fires

may have played in their timing, severity, location, and boundaries.

A. Hypothesis

The hypothesis of this dissertation is that

western Oregon patterns of 16th to mid-19th century Indian burning practices

had a direct effect on patterns of catastrophic forest fires that took

place from 1849 to 1951 in the Oregon Coast Range.

Indian burning practices are defined as those

uses of fire in pre-European American contact time ("precontact

time")

and early historical time that resulted in changed or stabilized landscape-scale

vegetation patterns. Three principal categories of these practices

are recognized: firewood gathering and burning, patch burning, and

broadcast burning (Zybach and Lake 2003). Firewood burning involves

the movement of fuels to specific locations

before burning, resulting in areas that contained relatively little

(or stockpiled) large, woody debris and designated spots of intense,

repeated

and prolonged heat. Patch burning is defined as having a specific

purpose and involving fuels within a bounded area, such as burning

an older huckleberry patch, a segment of trail, or a field of weeds.

Broadcast burning

is the practice of setting fire to the landscape for multiple purposes

and with general boundaries, such as burning a prairie to cure tarweed

seeds, eliminate Douglas-fir seedlings, expose reptiles and burrowing

mammals, and to harvest insects.

Maps, tables, and figures are used to show differences

in cultural landscape patterns resulting from Indian burning practices. Cultural

landscape patterns are landscape-scale designs created and maintained

by systematic human burning (and/or by other land management processes),

due

to their origin and appearance (Bailey and Winkler 2001). Landscape

patterns, for purposes of this dissertation, are considered at regional

(hundreds of thousands or millions of acres), basin (thousands or tens

of thousands of acres), and local (dozens or hundreds of acres) scales. These

patterns are shown to vary between northern, eastern, western, and

southern parts of the Coast Range due to differences in national and

tribal traditions,

topography, climate, vegetation, and distance from the ocean. The "cultural

legacy" of combined burning actions is shown to have a direct

effect on subsequent patterns of catastrophic forest fires in the same

region. Cultural

legacy is defined as the evidence of trails, savannah, prairies, fields,

berry patches, brakes, balds and other environmental indications of

human land uses that persist through time. Catastrophic fires

are defined as wildfire events that are greater than 100,000 acres

in size. Patterns

of burning and wildfire include similarities and differences in sources

and locations

of ignition; locations and extent of fire boundaries; timing, frequency,

seasonality, and intensity of fires; and effects of fire on local human

and wildlife populations.

The terms "Indian" and "American Indian" will

be used interchangeably to denote people who lived in the Oregon Coast

Range in precontact and early historical time, in accordance with current

and accepted use of these terms by the peers and descendents of these people. "Tribes" will

be used in the same manner as currently used by the Confederated Tribes

of Siletz, Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Coquille Indian Tribe, and

the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw. "Nation" will

be used to designate adjacent Indian tribes associated by proximity and

a shared language, such as the Chinook Nation of the 1940s that became

Chinook Indian Tribe, Inc. in 1953: specifically the Chinook and Athapaskan

nations on the Columbia, the Kalapuya and Athapaskan nations of the Willamette,

south Umpqua, and upper Coquille valleys, and the Koos, Siuslaw, Yakona,

and Salish nations of the coast. Tribes and nation names will attempt

to use the earliest accepted historical spellings, rather than modernized

spellings or European terms. "White" will be used to denote

predominantly European and American Caucasian immigrants to the Coast Range

in early historical time, with the acknowledgement that many of these people

were of Iroquois, Hawaiian, Chinese, or African ancestry. In this

instance, the term "white" is intended to represent people

of western European culture, rather than a particular race or skin

color.

Plants and animals are considered "native" to the Oregon

Coast Range if they were present in the environment before 1770. Species

are referenced by accepted local names, rather than "common" names (e.g.,

"boomer" vs. "mountain beaver"; "chittam" vs. "Cascara buckthorn"),

and are identified by their current scientific latin names in Appendix

A.

B. Physical

Setting

This dissertation concerns people, fire, and the use

of fire by people in a particular region of western North America. People

first entered the Oregon Coast Range more than 10,000 years ago, probably

by foot or watercraft. The use of fire by people in the region was

coincidental with their arrival; if people didn't arrive with fire, they

probably manufactured it within a few hours or days. The environment

began to be transformed immediately. For the first time ever, firewood

was gathered, forests were purposefully fired, and grasslands burned. As

human settlements became more permanent, so did patterns of human use upon

the land. This section briefly describes the history of the land

these people found, where they settled and why, and how the shape of the

land helped to shape the patterns of people and their fires across the

landscape.

A region's topography is largely a result of its geological

history. The formation of the Coast Range is relatively young compared

to other areas of the earth and of the Pacific Northwest. Its soils

and elevations are traced largely to the erosion of older landmasses, undersea

volcanic eruptions, tectonic plate uplift, and a series of cataclysmic

floods. According to Orr, et al. (1992: 167-202), the beginnings

of the Coast Range are thought to have been about 66 million years ago,

with underwater eruptions of basaltic pillow lavas that can now be seen

on the shoreline of Depoe Bay, throughout the Siletz River Gorge, and as

far east as Coffin Butte, along Highway 99 on the eastern boundary of Soap

Creek Valley. During the same period, the Klamath Mountains in present-day

southwest Oregon were steadily eroding, filling the shallow ocean to their

north with sediments that would ultimately become the Tyee soils and sandstones

of today. Ash and pyroclastics from infant Cascade volcanoes to the

east were added to the mix, and the steady collision of the Juan de Fuca

tectonic plate with the North American continental shelf forced the mass

to rise above sea level and moved the Pacific shoreline west. River

valleys and peaks were formed by erosion over millions of years; while

rising and lowering seas carved the western boundary and upland terraces. Lava

flows emanating from eastern Oregon 15 million years ago added further

definition to the Range. From 12,800 to 15,000 years ago, a series

of ice age floods coursed down the Columbia River, shaping the bluffs and

islands along the northern boundary of the Coast Range, and leveling the

floodplain of the Willamette Valley from Eugene to Oregon City with soils

from eastern Washington, Idaho, and Canada (Allen 1982). About

5,000 years ago the region achieved its current general configuration,

as melting

ice caused a worldwide rise in sea levels, flooding coastal river

valleys and creating the bays, estuaries, and beaches found today

(Orr, et al.

1992: 181-182).

These events all contributed to the topography of the

Coast Range, directly effecting patterns of human settlement and

land

use, including fire, from the time of discovery, more than 10,000

years ago,

to the present. In general, people have congregated and settled near

the mouths of most major rivers and bays, whether lesser villages and campgrounds

established along the low gradient areas accessible by canoe or other watercraft. Upland

prairies, brakes, berry patches, and grassy balds were heavily used on

a seasonal basis, and were connected by a series of ridgeline foot-trails. Fire

was daily, and depended entirely on gathered fuel in the heavily populated

areas and in seasonal campgrounds. Fire was used seasonally to burn

expanses of "root prairies", hunt, cure tarweed, rejuvenate

huckleberries, etc., in eastern oak savannahs and in upland prairies

and berry patches,

along ridgeline brakes, and southern slopes and balds.

Fire is said to behave according to ignition patterns

constrained by three sides of a "triangle," defined as

weather, fuels, and topography (e.g., Martin 1990: 58). In

general, shrubs, trees, and other forest fuels will burn more readily

and completely

in hot, dry weather driven by wind, rather than in cool, moist

weather or

in still air (ibid.: 59). Likewise, fire travels faster and

hotter moving uphill rather than down, covers the landscape more

completely

over rolling terrain rather than "skipping" across flatlands,

and tends to burn drier fuels on sunny south slopes rather than

shady north

slopes (ibid.: 58). Therefore, the topography of an area

has a controlling effect on local fire behaviors and helps to define

resulting

patterns of

burned and surviving vegetation. Topography includes slope

(steepness of terrain), aspect (which direction the terrain faces),

and elevation

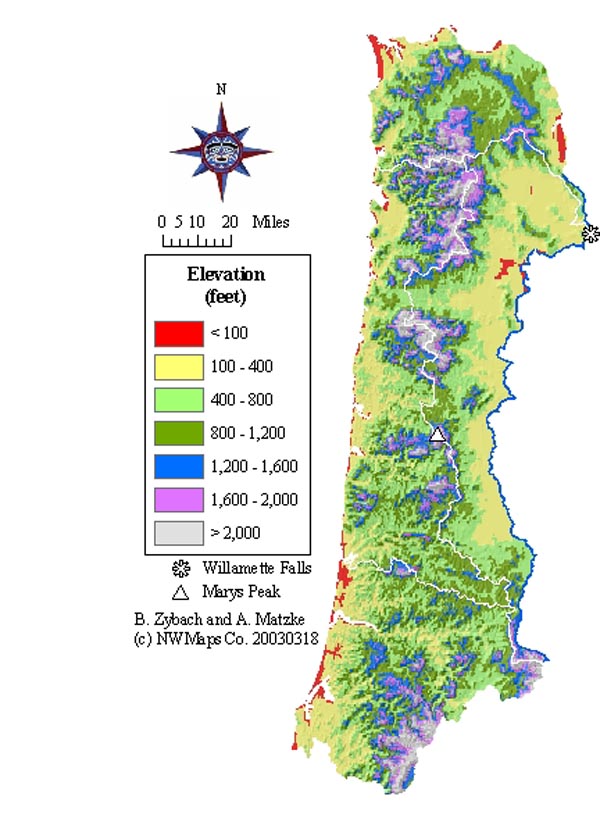

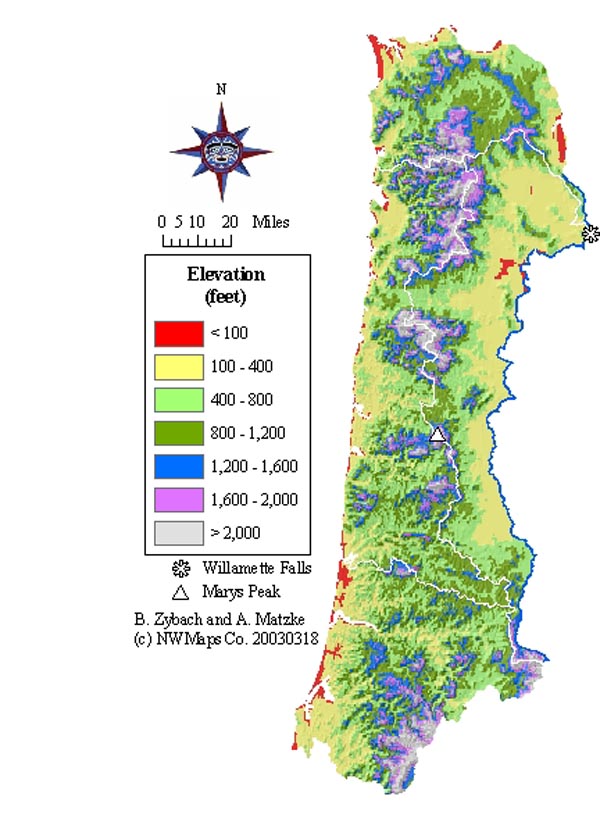

above sea level. Map 1.02 shows

the Coast Range as sloping steeply east and west from a central

north-south ridgeline that runs nearly its

entire length. On the west it is bordered at sea level by

the Pacific Ocean; the Columbia River is subject to tidal influence

along

its entire northern

border; and the Willamette Valley floodplain extends for miles

on a nearly flat plane along many portions of its eastern boundary. Its

highest point is near the center of the Range, where Marys Peak

reaches more than

4,000 feet elevation.

Map 1.02 Topography of the

Oregon Coast Range.

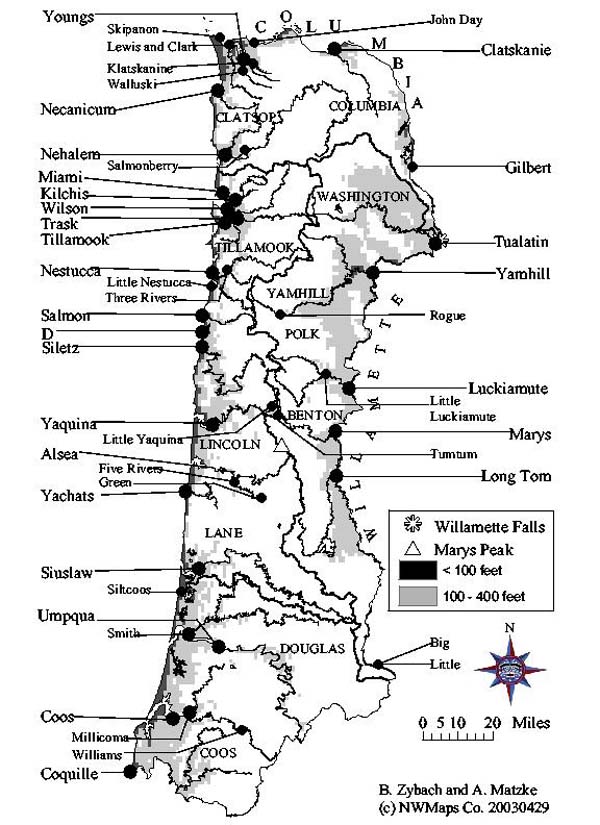

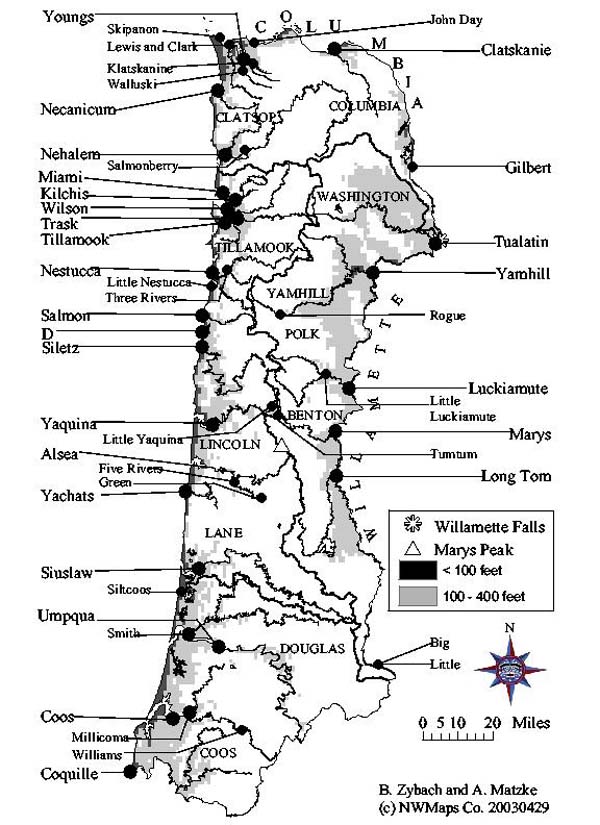

People prefer to live at the mouths of rivers and creeks

and to reside around bays and in valleys in the Oregon Coast

Range

for the same reasons they have always done so: freshwater; ready

transport;

access to terrestrial, marine and riverine foods; aesthetics. Currently,

most people who live in the Coast Range reside near the mouth

of the Willamette River, near the mouths of its tributaries,

near the mouth

of the Columbia

River, or along the bays and estuaries of coastal rivers (see

Map 1.03). Early

journalists (e.g., Howay, 1788; Lewis and Clark, 1805-1806; Alexander

R. McLeod, 1826-1828; Charles Wilkes, 1841) have reported similar

distributions

of people in early historical time; archaeologists (e.g., Strong: XX;

Hall: XX; Aikens: XX) have found the same patterns for prehistoric

time as well. Until recently, when people began to heat

their homes with electricity, steam, coal, and oil instead of

wood, and began to use automobiles

instead of feeding herds of ungulates for food or transportation,

areas of Coast Range settlement were quartered in grasslands, had relatively few trees, and most dead wood

was found gathered

or stacked for later use

in ovens, stoves, or firepits. No

evidence has been found that is contrary to this assessment, and it is

difficult to imagine a circumstance that would allow for much difference.

Map 1.03 Rivers and counties

of the Oregon Coast Range.

The fact that people become associated with the rivers

and valleys

they occupy is demonstrated by the names on the land of the Oregon

Coast Range. Rivers entering the Pacific Ocean from the east

are named Coquille, Coos, Umpqua, Siuslaw, Alsea, Yaquina, Nestucca, Tillamook,

and Nehalem; after the precontact communities that lived along their bays

and traveled their lengths by foot and canoe. Rivers that enter the

Columbia from the south are named Clatsop, Klaskanie, and Clatskanie for

the same reason. Rivers entering the Willamette from the west are

named Long Tom, Luckiamute, Yamhill, and Tualatin, also for the same reason. Even

the original historical name for the Willamette--Multnomah--was for a people

that lived on Sauvies Island, near the river's mouth. It is reasonable

to assume that most intensive firewood gathering, firewood use, trail development,

and patch burning in precontact time took place near the mouths of these

streams and along the low gradient areas most amenable to foot and canoe

traffic. Early historical records and early historical settlement

patterns support this assumption.

C. Climate

and Weather

The second side of the "fire behavior triangle",

after topography,

is weather. Weather is the

combination

of temperature, precipitation,

humidity, airflow, and related

phenomena (such as cyclones

and lightning) that is occurring

now; climate is the combination

of averages, seasonality, and

extremes of these elements

over time (Taylor and Hannan

1999).

Oregon Coast Range climate is classified

as a northern extension of

the Mediterranean climate that

characterizes coastal California,

with similar seasonal distributions

but cooler temperatures and

a longer rainy season. This

means the year has two general

seasons; a mild, wet winter

and a warm, dry summer. There

is little snow most years,

except for the highest peaks,

and that is usually melted

by late spring. Likewise, most

years have few--if any--days

that reach a 100 F. temperature

(Redmond and Taylor 1997: 34).

Most precipitation falls in the

form of rain during the "wet" season

from October to March, during which time most days are

cloudy and moist (Redmond and Taylor 1997: 28).

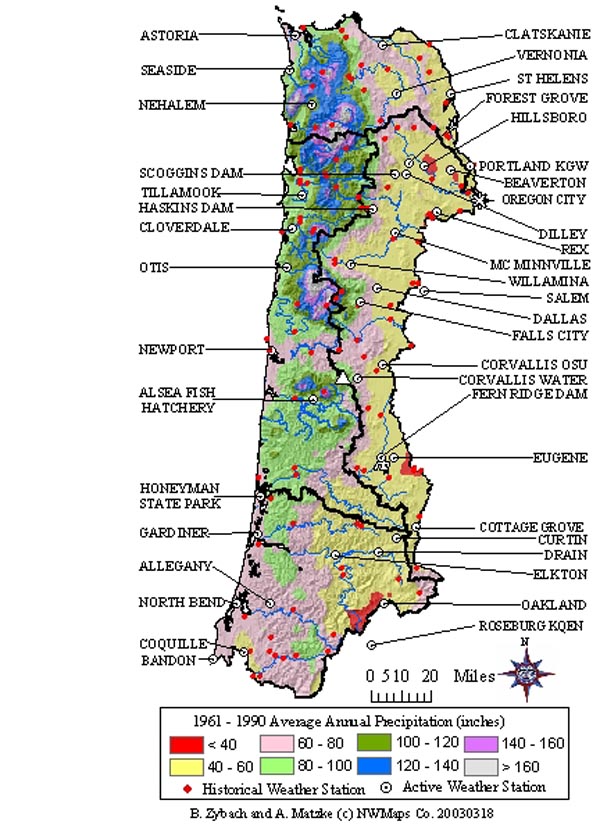

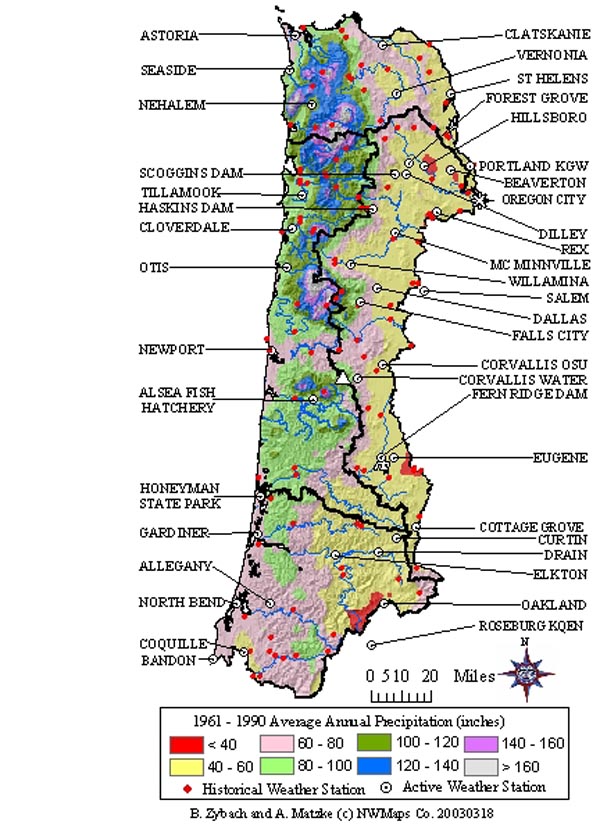

Map

1.04 shows average annual rainfall for the Oregon Coast

Range

for

a

30-year

period

from

1961

to

1991.

Notice

that

the

wetter lands

tend

toward the

northernmost

peaks

of

the highest

elevations.

The

driest

land is

in

the

eastern

Coast

Range,

and coastal

beaches

have

less

measurable

rainfall

(but

far more

fog),

than

Douglas-fir

forestlands

a few

miles

inland

and a

few

hundred

feet higher

elevation.

Snow.

The snows of 1861, 1881-82

(Lee and Jackson, 1984: 42)

and October, 1936 (Starker,

1939: 47) were all noted for

the vast amounts of livestock

they killed on the ranges of

the Willamette Valley and eastern

Coast Range. Prairie lands

that had been cleared and

maintained by Indian fires

had subsequently been kept

clear of tree growth by grazing

cattle, horses, sheep, pigs,

and goats. There is some evidence

that reductions in grazing

associated with the livestock

mortality of those years

resulted in the spreading

of Douglas-fir to many former

hillside pasturages (CITE).

Starker also mentions a "a similar wet

snow about twenty years previous" to

the 1936 event that apparently broke the tops and limbs

off a number of trees in

the Soap Creek area and covered the ground with debris from the breakage.

2) Temperature

and Humidity

Table

1.01 was

assembled

between 1961

and

1991

from

weather

data

stations

marked

with

white

dots

and

their

names

on

Map

1.04.

Locations

marked

with

red

dots

are

former

weather

station

sites

for

which

historical

records

are

available,

but

which

do

not

gather

data

at

the

present

time.

Map 1.04 Precipitation

of the Oregon Coast Range, 1961-1990.

Table 1.01 Oregon

Coast Range seasonal climate, 1961-1990.

|

Map 1.04

Location

|

"Killing

Frost" (28¡ F.)

|

Rain (7.0+

in.)

|

|

Annual Ave.

(in.)

|

Warm

(High Temp >65 F/mo)

|

Dry

(<3.0

in/mo)

|

|

Frost Free

Days

|

| |

First

|

Last

|

Fall

|

Winter

|

|

|

|

|

NORTH

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

First

|

Last

|

First

|

Last

|

Days

|

|

Astoria

|

Dec. 11

|

Mar. 3

|

Nov.

|

Feb.

|

66.42

|

July

|

Sep.

|

June

|

Sep.

|

283

|

|

Nehalem

|

|

|

Oct.

|

Apr.

|

121.74

|

|

|

|

July

|

Aug.

|

|

|

Oregon City

|

Dec. 6

|

Feb. 21

|

Dec.

|

Jan.

|

47.06

|

May

|

Sep.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

290

|

|

Portland KGW

|

Dec. 20

|

Feb. 3

|

Dec.

|

---

|

43.15

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

320

|

|

Seaside

|

Nov. 3

|

Feb. 19

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

74.46

|

June

|

Sep.

|

June

|

Aug.

|

284

|

|

St. Helens

|

Nov. 27

|

Feb. 20

|

---

|

---

|

42.76

|

May

|

Oct.

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

|

|

EAST

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beaverton

|

Nov. 26

|

Mar. 9

|

---

|

---

|

39.77

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

262

|

|

Corvallis

|

Nov. 26

|

Mar. 8

|

Dec.

|

---

|

42.67

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

263

|

|

Corvallis W.B.

|

Nov. 26

|

Feb. 16

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

66.13

|

May

|

Sep.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

284

|

|

Cottage Grove

|

Nov. 10

|

Apr. 14

|

Nov.

|

Dec.

|

45.54

|

May

|

Oct.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

210

|

|

Dallas

|

Nov. 12

|

Mar. 23

|

Nov.

|

Jan.

|

48.42

|

May

|

Oct.

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

235

|

|

Dilley

|

|

|

Dec.

|

Jan.

|

44.2

|

|

|

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

|

|

Eugene WSO

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Jan.

|

49.25

|

May

|

Sep.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

259

|

|

Fern Ridge

|

Dec. 1

|

Feb. 19

|

Dec.

|

---

|

41.63

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

286

|

|

Forest Grove

|

Nov. 12

|

Mar. 13

|

Dec.

|

Jan.

|

43.86

|

May

|

Oct.

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

245

|

|

Haskins

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

73.52

|

|

|

|

May

|

Sep.

|

|

|

Hillsboro

|

Nov. 16

|

Mar. 6

|

---

|

---

|

37.57

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

255

|

|

N. Willamette

|

Nov. 14

|

Mar. 13

|

---

|

---

|

40.78

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

246

|

|

Noti

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

60.65

|

|

|

|

May

|

Sep.

|

|

|

Rex

|

|

|

Dec.

|

---

|

41.37

|

|

|

|

Apr.

|

Sep.

|

|

|

Salem WSO

|

Nov. 2

|

Apr. 12

|

---

|

---

|

39.24

|

May

|

Sep.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

204

|

|

Willamina

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Jan.

|

49.96

|

|

|

|

May

|

Sep.

|

|

|

WEST

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alsea

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

92

|

|

|

|

June

|

Aug.

|

|

|

Cloverdale

|

Dec. 18

|

Feb. 3

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

84.04

|

June

|

Sep.

|

July

|

Aug.

|

319

|

|

Newport

|

Dec. 19

|

Feb. 9

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

71.72

|

Aug.

|

Sep.

|

July

|

Sep.

|

314

|

|

Otis

|

Dec. 12

|

Feb. 6

|

Oct.

|

Mar.

|

97.27

|

June

|

Sep.

|

July

|

Aug.

|

310

|

|

Summit

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

68.86

|

|

|

|

June

|

Sep.

|

|

|

Tidewater

|

Dec. 12

|

Feb. 9

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

91.42

|

May

|

Oct.

|

June

|

Sep.

|

307

|

|

Tillamook

|

Nov. 8

|

Apr. 6

|

Oct.

|

Mar.

|

88.65

|

July

|

Sep.

|

July

|

Aug.

|

216

|

|

SOUTH

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bandon

|

Dec.15

|

Feb. 9

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

58.91

|

July

|

Sep.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

310

|

|

Coquille

|

Nov. 27

|

Feb. 10

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

292

|

|

Curtin

|

|

|

Nov.

|

Dec.

|

49.82

|

|

|

|

May

|

Sep.

|

|

|

Dora

|

Nov. 28

|

Feb. 20

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

283

|

|

Drain

|

Dec. 4

|

Mar. 9

|

Nov.

|

Jan.

|

46.17

|

May

|

Oct.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

270

|

|

Elkton

|

Dec. 17

|

Feb. 9

|

Nov.

|

Jan.

|

52.17

|

May

|

Oct.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

312

|

|

Honeyman

|

Dec. 19

|

Feb. 2

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

76.01

|

June

|

Sep.

|

June

|

Sep.

|

321

|

|

Idleyld

|

Nov. 10

|

Apr. 5

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

63.54

|

May

|

Oct.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

219

|

|

North Bend

|

Dec. 28

|

Jan. 29

|

Nov.

|

Mar.

|

63.48

|

July

|

Sep.

|

May

|

Sep.

|

334

|

|

Riddle

|

Dec. 11

|

Mar. 6

|

---

|

---

|

30.11

|

May

|

Oct.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

281

|

|

Roseburg

|

Nov. 25

|

Mar. 1

|

---

|

---

|

32.44

|

May

|

Oct.

|

Apr.

|

Oct.

|

269

|

|

Sutherlin

|

|

|

---

|

---

|

41.13

|

|

|

|

May

|

Oct.

|

|

Burning seasons.An

analysis

of Table 1.01 shows a tendency toward four seasons in the Coast

Range: a) a warm, wet spring/early summer of

low

fire

hazard

due to air moisture, soil moisture, and fast growing trees

pulling massive amounts of water from the ground and transferring

it to the air through transpiration; b) a hot, dry late

summer/early fall with moisture stressed plants, dry soils,

desiccated

grasslands with high fire hazard potential,

especially on an east wind; c) heavy fall rains, knocking

desiccated

plants and leaves to the ground, filling rivers

and

creeks with water and fish; and d) killing frosts, desiccating

brackenfern prairies and woodland shrubs and trees, mostly

wet or frozen, but fires can spread on occasional east

winds, particularly through brakes, across unburned balds, brush

piles, and south-sloping berry patches.

Drought. The seasonal

droughts of the Pacific Northwest have been noted as one of

the primary factors favoring conifer forests over hardwood

forests in the region

(Franklin and Dyrness 1988). Many deciduous trees simply cannot

survive

long,

dry

summers without periodic irrigation (CITE). Graumlich (1987)

analyzed tree rings to arrive at a 300-year precipitation

pattern

that identified specific years (1717, 1721, 1739, 1839, 1899,

1929, and 1973) and

at least one decade per century (1790s, 1840s, 1860s, 1920s,

and

1930s) of prolonged regional drought. The annual events don't

seem to have a significant relationship to Coast Range fire

history, but

the prolonged droughts correlate closely with major forest

fire events (see Chapter 4).

3) Lightning

The entire Coast Range has remarkably few

lightning strikes or storms compared with

the remainder of the Pacific Northwest (Morris

1934; Kirkpatrick 1939: 28), and the first

reported lightning caused fire in the area

didn't occur until 1927 (Kirkpatrick 1939:

31). This is an important consideration

for this study because of the region's history

of forest fires and the existence of numerous

early historical prairies, meadows, brakes,

and balds in Alseya Valley. These landscape

features could have only been made and maintained

through regular Indian burning--no other

cause can be identified.

Passed over some beautiful farming lands low grumbling thunder heard at

a distance and I think this is the third time I have heard thunder in

the Territory as thunder and Lightening is varry rare From what cause

I cannot tell it may be possibly on account of the lowness of the clouds

which rest on the mountains and in fact on the earth even in the vallies

---James Clyman, June 4, 1845

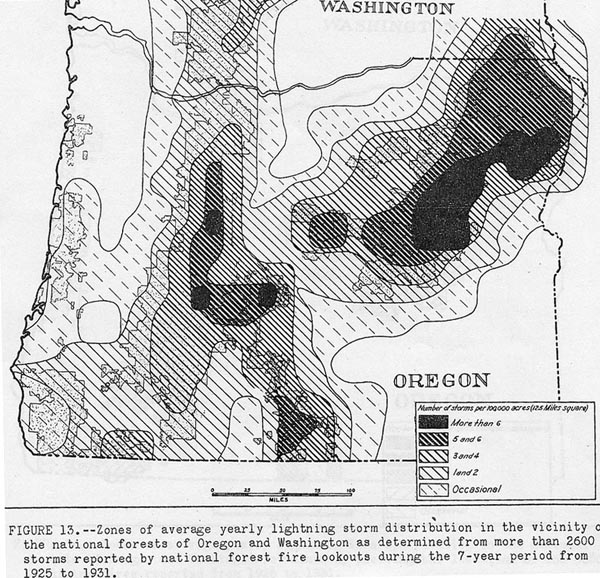

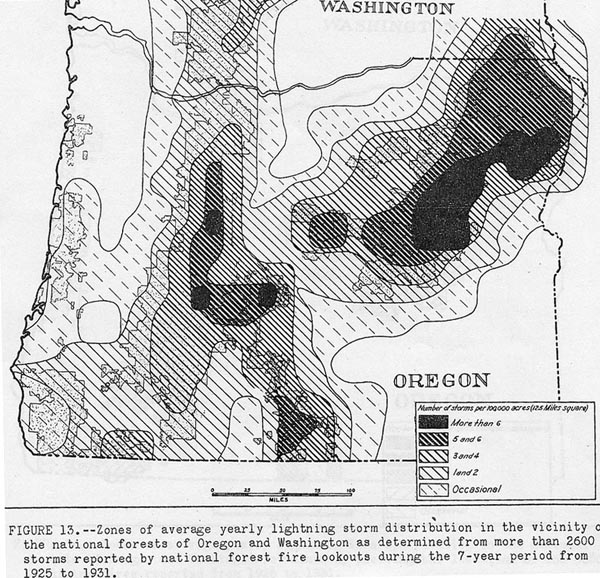

Map

1.05 Shows the locations of more than 2,600

lightning

storms recorded over a seven-year period in

Oregon, from 1925 to 1931. Note the pattern from

southwest, in the Biscuit fire area of the Klamath-Siskiyou

Mountains, to the northeast, along the crest

of the Cascade Range, thereby almost entirely

missing the Coast Range.

Map

1.06 Shows the locations of all lightning

strikes

recorded in Oregon over a five-year period, from

1992 to 1996. Note the remarkably few number

to strike in the Coast Range, although strikes

are common throughout the Klamath-Siskiyous,

and along the crest of the Cascade Range.

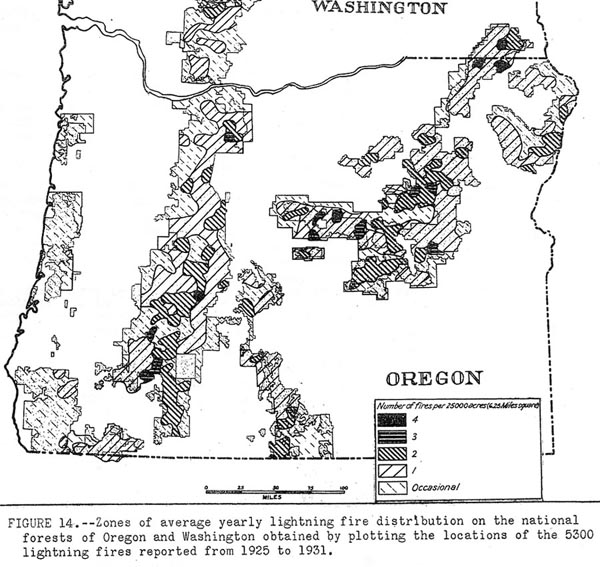

Map

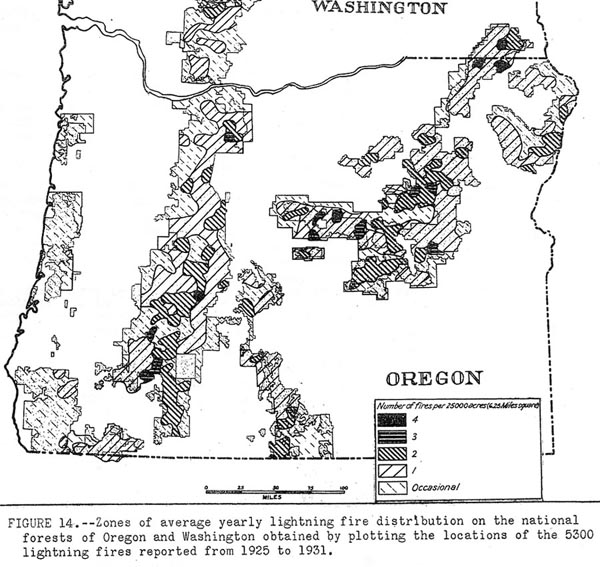

1.07 . Shows the

location of 5,300 lightning fires

in Oregon mapped over a seven-year

period

from 1926 to 1931. Note the relatively

large number of fires in the

Klamath Siskiyous, and along the

crest

of the Cascade Range, and

the almost complete absence

of lightning caused fires during

the same time period in the

Coast Range.

Map 1.06 Lightning

strikes in Oregon, 1992-1996.

Map

1.07 Lightning fires in Oregon, 1925-1931.

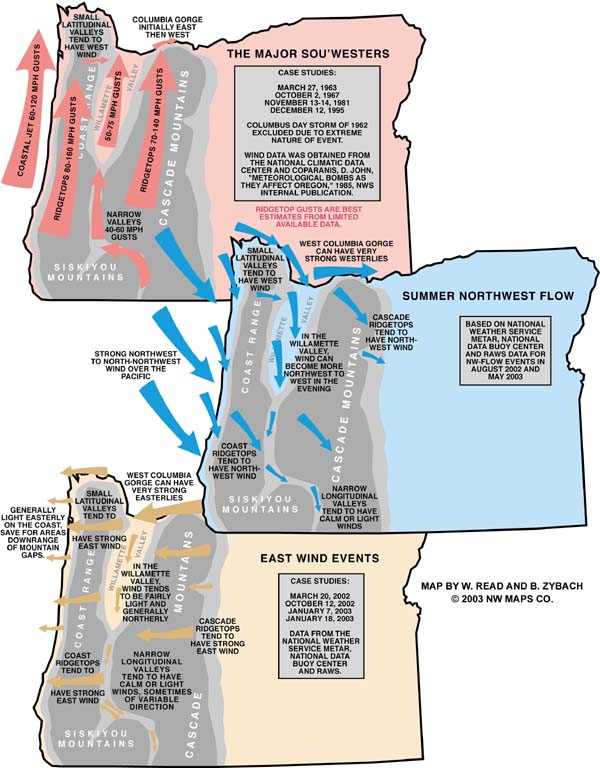

4) Wind. The Columbus Day Storm of

1962 traveled due north from California to southern Washington,

including the Oregon Coast Range in its path. Over 11 billion

feet

of commercial timber were estimated to have been blown

down during

the course of this event (Lucia, c.1963: 50). In April,

1931,

a "dust storm" blew in from the northeast, spreading

wildfires

through coastal forests and farms (Grant, 1990: 7) and

causing a homefire at the southeastern base of Coffin

Butte to

blow

charred shingles "1/4 to 1/2 mile toward" the

southwest (Rohner and Rohner, 1993: 5). This storm was

noted by residents in

both Lincoln and Benton counties as a heavy east wind

bearing so

much red "alkali" dust from "eastern Oregon" that

it

caused the day to become dark and people to become "scared,

it

was so eerie" (ibid.: 5). .

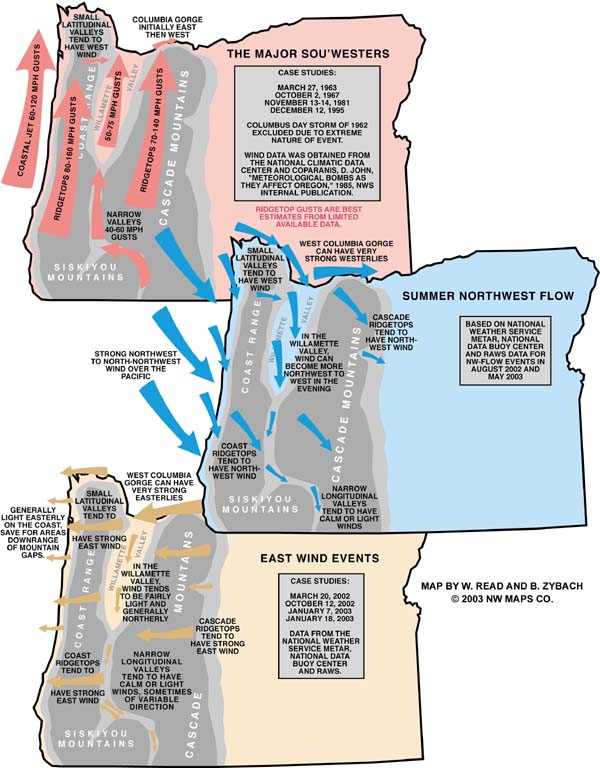

Map 1.08 Prevailing

wind patterns of the Oregon Coast Range.

D. Vegetation

and Fuel Patterns

The final side of the "fire behavior triangle," after

topography and weather, is fuel. For forested

areas, trees and shrubs form the

bulk of available fuel. For grasslands,

shrublands, and prairies, grasses,

ferns, and brush species comprise

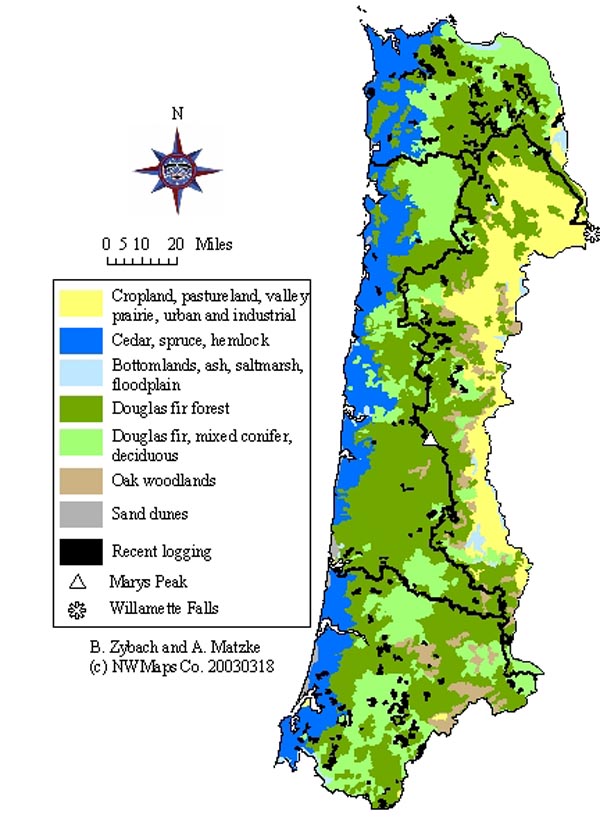

most available fuel. Map

1.09 shows

the north-south distribution patterns

of the principal wildfire fuel types

of the Oregon Coast Range. Three types of

patterns dominate: along the coastal "fog-belt",

Sitka spruce, western hemlock, and

redcedar are the primary conifer

trees and red alder and bigleaf

maple are the major broadleaf species;

the eastern Coast Range is dominated

by the cities, towns, and farms

of the Willamette and Umpqua river

lowlands,

with native and exotic grasses,

ferns, white oak, black cottonwood,

and Oregon ash forming most of the

available fuel in unmanaged

areas; the remaining

central part of the Range is dominated

by some of the largest and fastest

growing mixed and "pure" stands

of Douglas-fir in the world, stretching

northward from the Middle Fork Coquille

and extending through

the wettest and steepest lands of

the Coast Range in an unbroken conifer

forest that reaches completely to

the Columbia River, straddling all

four subregions and connecting them

all together with a nearly unbroken

shifting mosaic of some of the largest

and fastest growing conifer

trees ever measured. These are

also the ingredients for

some of the largest and most destructive

forest wildfires in history--massive

amounts of living and dead, pitchy,

conifer fuels, grasses, and

ferns per acre for tens of thousands

of contiguous acres; an unbroken,

rolling topography that stretches

from north to south the entire length

of the region; and seasonal droughts,

often accompanied by low humidity,

hot temperatures, and dry, east

winds.

Map 1.09 Native

vegetation patterns of the Oregon Coast Range.

The three principal "fire triangle" components

of wildfire and controlled burns are fuel, weather, and topography. All

else that is needed

is a source of ignition. The Oregon Coast Range has

abundant forest and grassland fuel, regular seasonal droughts and wind

patterns that are ideal

for landscape-scale burning practices and wildfire events;

a long history of both, and a varied topography that includes large expanses

each of

flat, sloping, steep, and heavily dissected terrain.

Every hour, day and year people start and/or maintain thousands of fires

in a systematic arrangement

that borders and crosses the entire Coast Range landscape;

typically in patterns that reflect the spatial demographics of the population

at any

given point in time.

From

the late 1400s until the late 1840s, and for a period

of time likely extending more than 10,000 years

before then, the Coast Range

was populated by a wide variety and large number of

native

American Indian cultures, all

of whom undoubtedly used fire skillfully on a daily

and constant basis. The history of forest wildfires

for this

period is incomplete, but a

great deal can be inferred

by the trails systems, expansive

prairies, oak savannah, wild berry patches, and other "cultural

legacy" left behind by these people.

From 1849 through 1951,

a series of catastrophic forest fires took place in the Coast Range

that transformed

100s

of thousands of forested acres to charred snags. Wildlife habitat

was

often burned at a rate of tens of thousands of acres a day during

the

course of these Great Fires. From 1952 until 2003, only a few Coast

Range

fires occurred that could be termed "large", and none

approached 100,000 acres in size. This thesis addresses

the question of whether the use of fire across the landscape by Indian

people over the

span of 350+ years prior to 1849, had any relationship

to a subsequent series of catastrophic forest fires, that lasted until

1951. Specifically,

were their differences or similarities in the seasonal

timing of large scale fires? Common or differing causes and locations

of ignition? Common

or differing burn boundaries?

To

better answer this question,

the entire region was divided

into four subregions: North,

East, West, and South

for comparison. Each has distinct drainage

patterns, weather patterns,

vegetation patterns, and human

use and settlement

patterns; both in precontact

and historical time.

North

is dominated by the Columbia River, the Willamette

River from the Falls to its mouth, the heavily

dissected terrain of the Nehalem River basin, and

Clatsop

Spit. It is mostly forested with conifers: spruce,

hemlock, cedar

and shorepine on the western edge, and Douglas-fir

dominated forests throughout the remainder, with

oak appearing in groves

and scatterings as far west

as Oak Point, at Fanny's Bottom, an old Klaskani

townsite. Annual spring floods,

caused by the melting snows of Rocky Mountain and

Cascade Range glaciers

and snowpack, regularly inundate and erode the banks

of the Columbia.

Daily tides reach the entire northern length of the

Coast Range,

from Astoria to Portland, and extend along its entire

western, Pacific

ocean, boundary. Its

southern boundary is dominated by Saddle Mountain,

one of the wettest

areas of the Coast Range; its eastern boundary is

dominated by Sauvies

Island, one of the driest and most regularly flooded

areas of the Range.

East

is dominated by the floodplains and upland prairies

of the Willamette River, with oak, cottonwood,

willow, and other deciduous trees being the most

widespread

species. Douglas-fir and some true fir forests dominate

the western peaks

and valleys of the subregion; which are

entirely drained by a north-south series of west

to east flowing rivers that empty into the Willamette

River;

which forms the eastern boundary of the region. Elevation

ranges from

the grassy balds of Marys Peak, at over 4,000 feet

elevation, to

Willamette Falls, whose pool is not too much

above tidewater. East is the driest, flattest, and

most generally low elevation (below

400 feet) of the subregions; it also has the least

amount of conifer

forest and some

of the poorest soils and weather for Douglas-fir

and hemlock.

West

is dominated by the Pacific Ocean along its

entire

western boundary; Marys Peak along its common

ridgeline boundary with the eastern subregion; Tillamook

Bay

to the north and Table Mountain to the south. Tideland

is usually either

rocky or sandy, often lined with a thin strip of shorepine, usually

only a few hundred yards wide and rarely a mile

wide.

To the immediate east the shorepine is another north-south

strip

of spruce-hemlock forest, that extends as far inland as the fogbelt

climate it requires for

dominance. Inland from the coastal fogbelt

forest, and extending throughout

the remainder

of the subregion, is a great north-south swath of

Douglas-fir forest

that is the setting for some of the fastest growing conifer forests

in

the world and some of the largest and most memorable

forest fires

in history. The highest peaks and ridgelines are

often characterized

by grassy balds,

brackenfern prairies, and occasional stands

of true fir trees.

South

is defined by the mainstem Umpqua River

Valley,

the

coastal cranberry bogs, and the Port Orford

and myrtlewood forests of the Coos and Coquille

river

basins.

Coos Bay was the scene of some of the first

extensive clearcutting and

sawmilling in the Coast Range, when those

industries

were undertaken

to help satisfy the rebuilding of San Francisco

and

the expansion of region-wide goldmining in the early

1850s.

In 1868, the Coos Fire consumed more than 100,000

acres of prime timberland in just a few

weeks time. South is dryer, warmer, and lower in

elevation than West

or North, but

wetter, cooler, and generally higher in

elevation

that East. The

Umpqua Valley area was inhabited by Kalapuyan

people

who maintained an oak

savannah similar to the savannah maintained

by other Kalapuyans in the

Willamette Valley. Black oak and tanoak are

more

common in the southern region, though,

while white

oak is the most widespread tree species

in the East; and no species of oak is common

throughout most of

the western and northern subregions.